In the chaos of covid, coughs, colds and constant change, I decided to seek some calm each day, and collect a library of books to share with you for the Twelve Days of Christmas. Here is the collection in reverse order, starting with 12 drummers drumming culminating with the partridge in the pear tree!

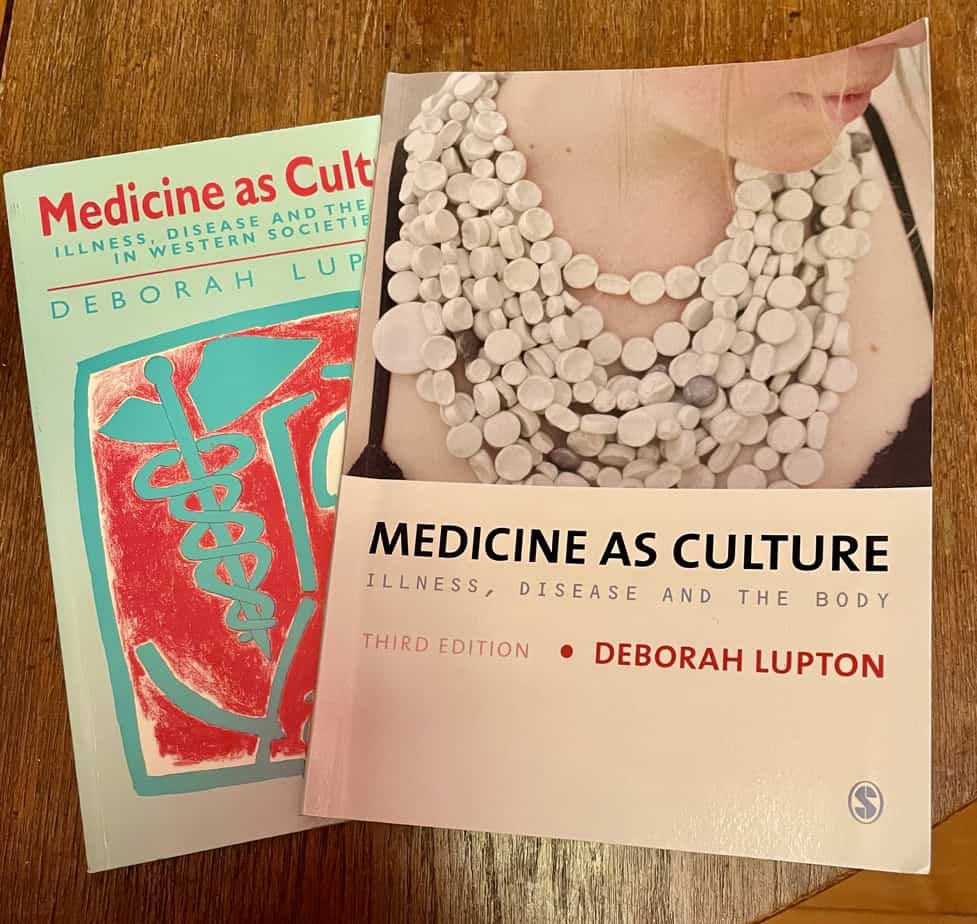

On the twelfth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

Medicine as Culture, by Deborah Lupton

I love browsing in Oxfam books, it’s the possibility of discovering a book that changes the way I see the world that pulls me through the door. This book is one of my best finds. The 1994 edition was so useful to my understanding of illness that I went on to invest in a new copy of the 3rd edition.

This is a resource for health professionals who want to improve how they care for people who are ill. The causes of illness are explored from a wider perspective that is usually offered in medical textbooks. With a specific focus on how patient expectations can be managed in the context of the complex multicultural societies we inhabit. A doctor needs to have medical knowledge and skills and to be able to communicate, but the third part of the paradigm is being able to understand the patient’s illness perspective; this will enable them to help the patient manage their life with illness.

The author explores two other themes that are particularly important to consider in both the undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum: the doctor as part of the therapeutic relationship and the power dynamics that exist in any clinician-patient relationship.

‘It is important to recognise that doctors and other health-care professionals bring their own cultural beliefs to the medical encounter, generated not only by their scientific training but also by other aspects of their own lifeworld.’

The chapter on Power Relations and the Medical Encounter is a particularly topical read as in addition to exploring the power dynamic between professional and patient, it considers the consequences of medicalising normal life challenges; which has the consequence of passing the responsibility of resource provision from individuals and politicians to the health service. This chapter provides the material for a teaching session or tutorial, you could use the art resources on Power on this website to aid your thinking and discussion.

On the eleventh day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

The Sleeping Beauties and Other Stories of Mystery Illness, by Susanne O’Sullivan

It’s interesting how reading one book leads to the discovery of another, pretty soon a library of books sharing a connection sits on your shelf.

This book appeared next in my reading list because it linked to an earlier read in which the author considers how migrants cope with their changed circumstances. The ‘The Sleeping Beauties’ are a group of refugee children who on arrival in Sweden, a place of safety, fall asleep, unable to be woken, perhaps protected from the reality of the events that led them to become refugees. Their plight continues, untreated and unresolved, cared for by family and local the local community, recovery only occurring when the children receive settled status.

The book is a collection of international stories, collated and expertly narrated by Susanne O’Sullivan a consultant neurologist with specific expertise in functional illness. In a world where what we see down a microscope or read reported in terms of mmol/l shapes our understanding of illness, O’Sullivan reminds us that external events in our communities and culture also have the potential to shape our experience of illness. The book is an interesting read for non-medics as it explores many topical health stories, such as the Havannah Syndrome in Cuba. It’s an essential read for any clinician or medical student as the concept of functional illness does not fit neatly with the dogma of western medicine, is often excluded by clinicians from the differential diagnosis and is rarely accepted by patients. It is an easy read and a great resource for a tutorial or teaching session.

The stories and O’Sullivans analysis helped me to think more clearly about functional illness and provided another piece of evidence to support the importance of living in a caring and compassionate community.

On the tenth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

Klara is not human; she has been created to be an artificial friend. The story explores the world of human relationships as seen through her non-human eyes.

You maybe be familiar with Nobel Prize-winning author, Ishiguro’s work through reading or watching Remains of the Day, a unique view of the British aristocracy and their servants. I’ve always been astounded that Ishiguro who is Japanese could write such a perceptive novel. The power of his work is not in romanticising or politicising the underdog but in narrating the story eloquently from both perspectives. Social class may no longer be considered a prominent aspect of British culture today, but it still contributes to the inequity of opportunity. Many of his novels discuss the same theme of social apartheid e.g. in Never Let Me Go, he explores the lives of a group of children bred purely for their organs.

In my naivety, I’ve always associated AI with robots in human forms, like Klara, created to undertake human tasks. This view was dispelled by listening to the 2021 Reith Lectures and the associated radio series Rutherford and Fry – Living with AI (both on Radio 4 and worth listening to on BBC Sounds). Stuart Russel argues that it is the things we cannot do as humans that we should be engineering AI to do, leaving people to undertake the interpersonal care that is what being human is all about.

Have you ever considered how much AI is already woven into your life?

You might think that AI is neutral but there are numerous examples where biases introduced by programmers have the potential to influence many aspects of our lives from shopping, job interviews and if we use dating Apps, who we chose as a life partner.

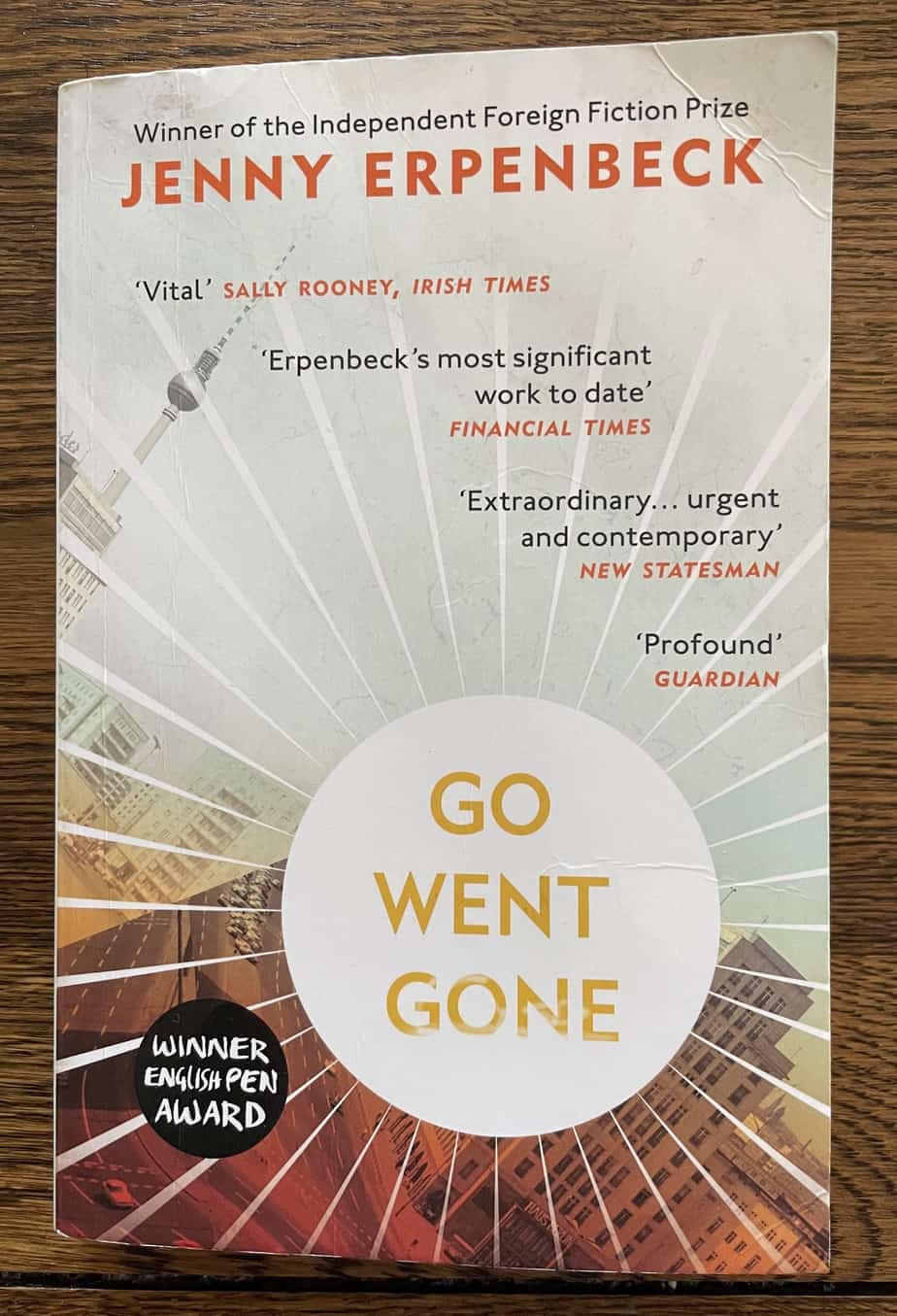

On the ninth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

Go Went Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck

Go Went Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck

The plight of asylum seekers is an increasingly common literary theme in contemporary literature. I must remind myself that although many stories are fictional, they reflect the real experience of thousands of people. They are important because they keep a spotlight on the refugee crises and raise awareness about the underlying causes of mass migration. Keeping this issue alive in our hearts and minds and in the media maintains pressure on those who do have the power to make positive change.

The author grew up in a divided Berlin, she tells the story of Richard a retired academic who lives in contemporary Berlin. He lives a safe sheltered life blinkered to the experiences of refugees happening a stone’s throw from his flat. When Richard eventually sees the refugees, camped out in a local square, forbidden to work or to settle, he befriends them and starts to explore who each of them is, seeing them as individuals with families, fears, hopes and dreams. This book is about the human issues of migration.

(GP School Art Club February 2022 will be discussing the theme of migration and health)

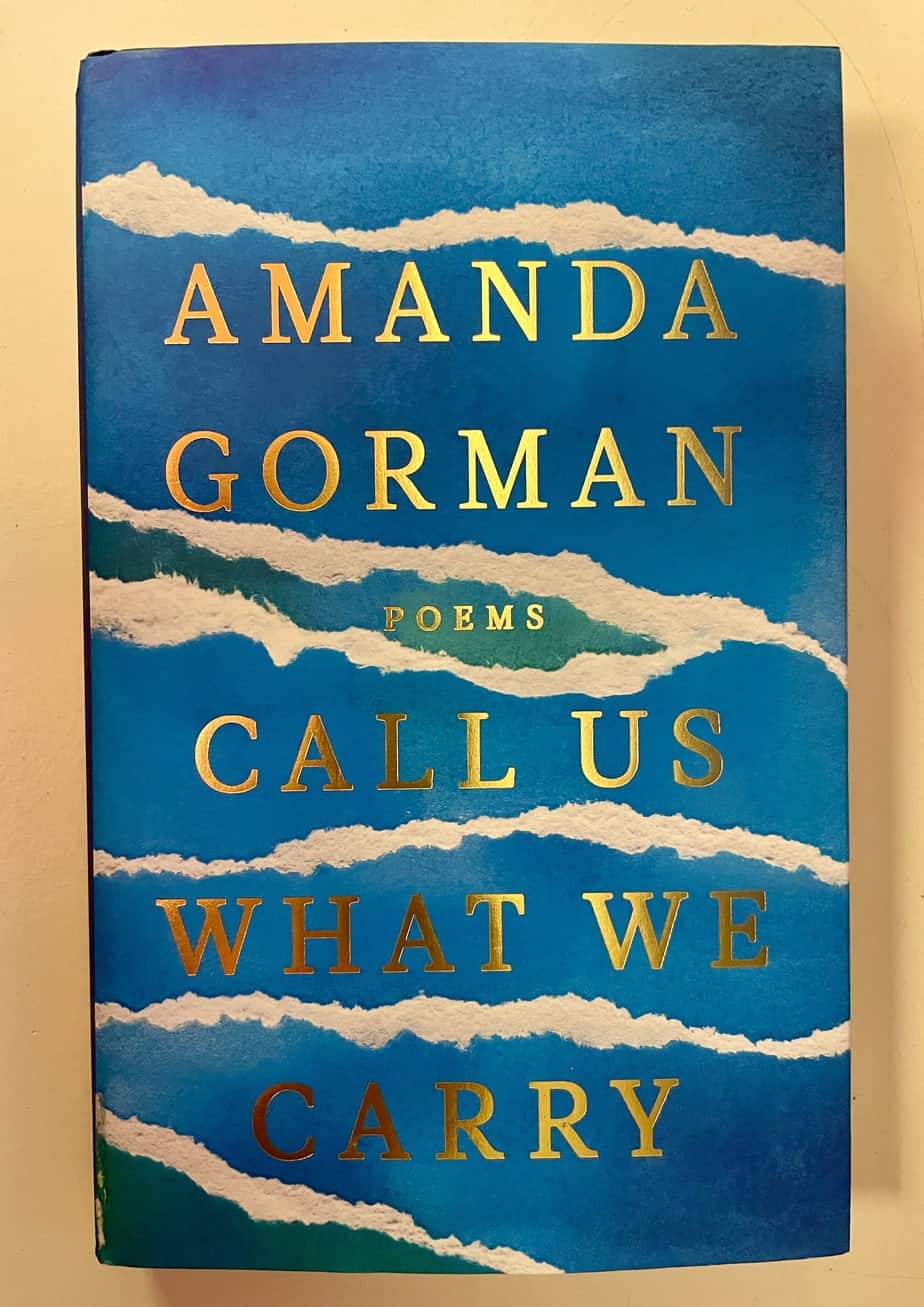

On the eighth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

Call Us What We Carry, poems by Amanda Gorman

New Year should start with a feeling of hope, and this is the focus of the book of poems, by the young American poet, Amanda Gorman.

We cannot possess hope without practising it. (Every Day We Learn)

It’s hard not to feel moved by her advocacy for a better world reflected so eloquently in her words. Some poems more like speeches describe the anger, fear, frustration, pain and challenge of living in a pandemic.

Others are a quiet narrative, calming the mind.

A book for @Emergencypoet to prescribe to all from her Poetry Pharmacy.

The anthology includes the poem ‘The Hill We Climb’ which was recited by Amanda at President Biden’s inauguration. You can listen to it here.

If you like her poems then listen to her ‘New Day’s Lyric’ shared last night to mark 2022.

I like the way, her words wash over me, reminding me of a poem by Rumi.

Story Water

A story is like water

That you heat for your bath.

It takes messages between the fire

And your skin. It lets them meet,

And it cleans you!

Very few can sit down

in the middle of the fire itself

like a salamander or Abraham.

We need intermediaries.

A feeling of fullness comes,

but it usually takes some bread

to bring it.

Beauty surrounds us,

but usually we need to be walking

in a garden to know it.

The body itself is a screen

to shield and partially reveal

the light that’s blazing

inside your presence.

Water, stories, the body,

all the things we do, are mediums

that hide and show what’s hidden.

Study them,

and enjoy being washed

with a secret we sometimes know,

and then not.

Wishing everyone reading this a happy and healthy 2022.

On the seventh day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

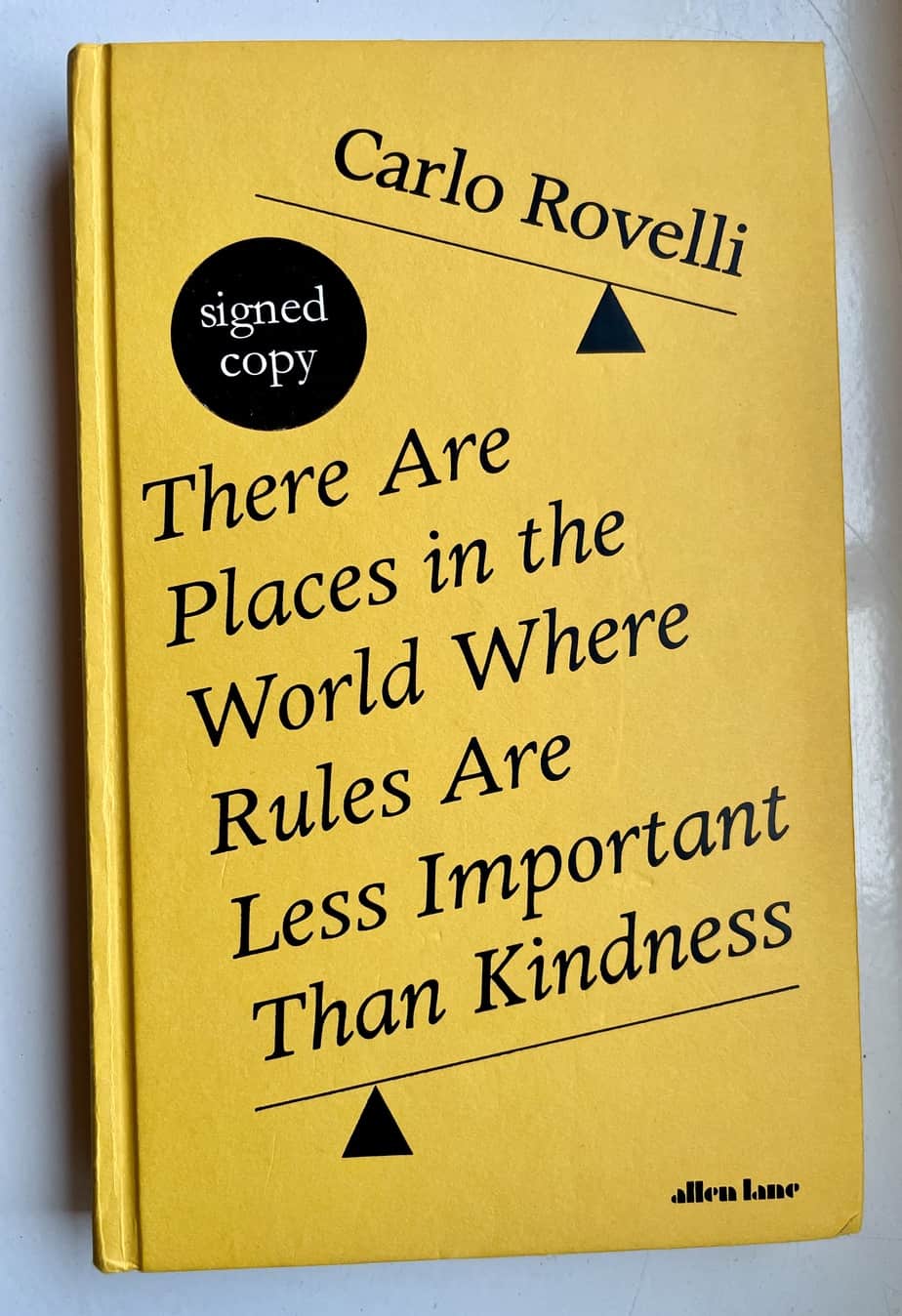

There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness, by Carlo Rovelli

As you might imagine I am surrounded by piles of books. The simple task of picking a book a day for the 12 days of Christmas has become more complicated with the task of choosing the right book seeming more important than when I first started 7 days ago. The booklist has become a narrative or perhaps even a diary of important occurrences in 2021 and priority issues for 2022.

So, what to select for New Year’s Eve, the 7th Day of Christmas.

No parties tonight just a quiet night in with loved ones, reflecting on the year and discussing hopes and aspirations for 2022. No better book to choose than one that is a series of reflections from one of the most inspiring thinkers of our time.

Rovelli is a theoretical physicist who grew up in the beautiful city of Verona. He currently thinks and works at the Centre De Physique Theorique in France. So why choose a book by a theoretical physicist? The same curious mind that has developed knowledge in the arena of quantum gravity is also continually questioning and writing about received knowledge in other spheres of learning. Rovelli values the differing perspectives that other disciplines – art and philosophy bring to scientific discovery. Promoting what this website is trying to achieve in showing how a curiosity for creativity and art can enhance the care a doctor provides. His writings reinforce the importance of standing on the shoulders of giants to gain new perspectives.

The book is a collection of published reflections on many varied topics- philosophy, probability and global warming, about many learned individuals- Einstein, Darwin, Nabokov, and Churchill but mostly it’s about the humility of learning and being human.

Rovelli says, science is a continuous process of exploring novel possible views of the world; this happens via a “learned rebellion”, which always builds and relies on previous knowledge but at the same time continuously questions aspects of this received knowledge. The foundation of science, therefore, is not certainty but the very opposite, a radical uncertainty about our own knowledge, or equivalently, an acute awareness of the extent of our ignorance.

Feeling comfortable with managing uncertainty is a valuable skill for all doctors. The chapters in which Rovelli explores this challenge are masterful and surprisingly reassuring.

Between certainty and complete uncertainty, there is a precious intermediate space – and it is in this intermediate space that our lives and our thoughts unfold.

Uncertainty is not the enemy.

We cannot get rid of it. We can diminish it. We should not experience it as some sort of nightmare. On the contrary, we should be reconciled to it as our lifelong companion.

We are limited and mortal, we can learn to accept the limits of our knowledge – but we can still aim to learn and to look for the foundation of this knowledge. It is not certainty. It is reliability.

Powerful and helpful advice.

The penultimate chapter is ‘A Day in Africa’ and it is this reflection on a life experience that gives the book its title. Can you think of a time when it was more important to be kind than it was to follow the rules? An important ethical question, one that would make a great tutorial.

Thank you to @ToppingsEdin for displaying this book in a place where it caught my attention.

Hopefully what I’ve written will catch your attention and persuade you to of the value of reading this in 2022.

On the sixth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

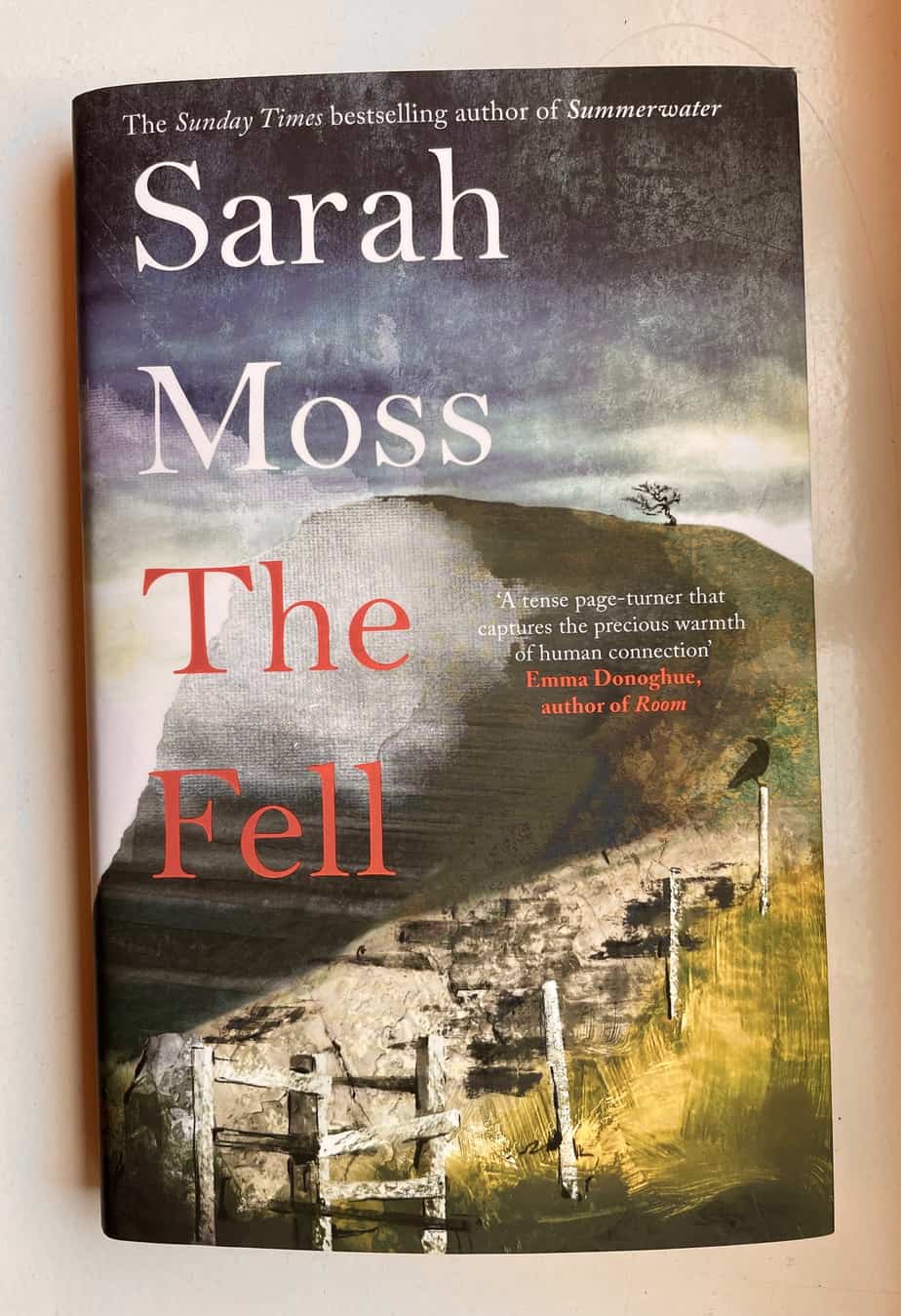

The Fell, by Sarah Moss

Deep in the middle of the first lockdown, I remember reading a media article that questioned whether Covid would feature in contemporary literature? Would people want to be reminded of the pandemic? Would it impact our lives significantly enough for it to need to be mentioned? These questions now seem naïve. It would be unthinkable to write a novel set in 2020 and 2021 without Covid being part of the narrative.

As I’ve had said earlier in this blog, stories help us make sense of our experiences and the world in which we live. Books written today about today will act as a historical record of our personal and collective experience of living through the pandemic.

I rarely buy a hardback book but having read about The Fell in @guardianreview I wanted to read the book ‘in time’ and not ‘after time’.

The Fell asks probing questions about the place the world has become since March 2020, and the place it was before. This novel is a story about compassion and kindness and what we must do to survive.

Alice (the main character) wonders if “maybe she’ll die without ever touching another human”,

The story that flowed from the thick smooth pages felt so immediate, both intimate and a reflection of the wider community experience of Covid. There is more to the book than just the impact of Covid on life, the descriptions of nature in the Pennines are felt and smelt, especially the dampness and that feeling of rain running down your neck, invading a protective waterproof. What I enjoyed most about The Fell is that it is a story about normal people in extraordinary times. Like a drop of ink in water, the pandemic has permeated everything, and this feeling is transmitted from author to reader. The themes are broad but personal; loneliness, isolation, fear, confusion, and inequality. How do you live with the new normal, what rules are acceptable to break and is it ok to ask the person who is doing your essential shopping to buy you a packet of hula hoops? As in many of Sarah’s books, the most thought-provoking narrative is how she explores the consequences of the decisions we make, some poorly judged some innocently made.

There is a lot of learning for the medical reader about being human.

Read more about The Fell in @emmabrokes review, or buy/borrow to provoke your own thoughts.

On the fifth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

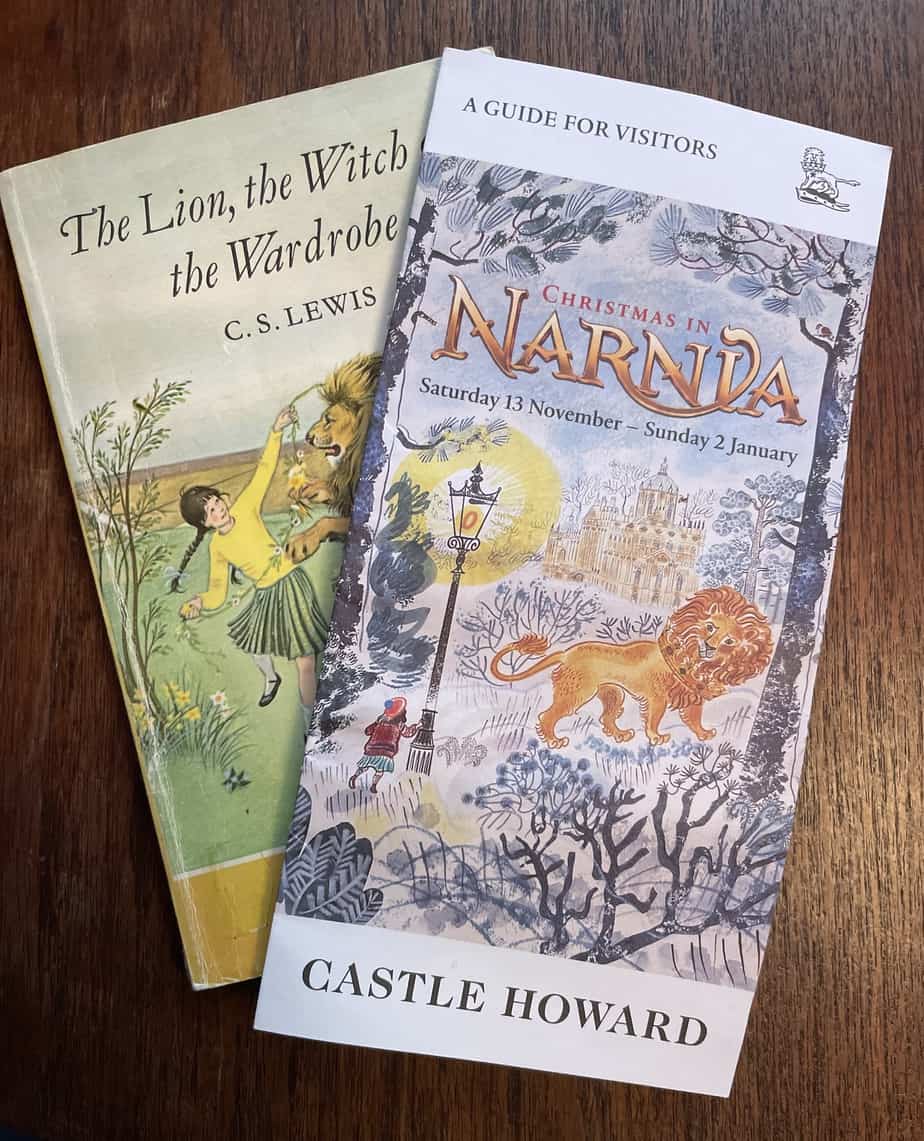

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by C S Lewis

Think back to the last time you played hide and seek- can you remember where you hid? Was it at the back of a wardrobe sitting on dusty shoes with musty clothes pressed against your face?

Now close your eyes and remember the last time your imagination took you somewhere else, where did it take you and what do you remember?

Yesterday I took my grown-up children to Castle Howard and stepped through a large imposing mirrored wardrobe door into the imagined world of Narnia. I was transported back into the story I remember from childhood.

C S Lewis spent a large part of his childhood alone with books, he said he was the product of long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstairs indoor silences, attics explored in solitude, distant noises of gurgling cisterns and pipes and of endless books. When his elder brother was home, they spent their time inventing imaginary worlds. There are seven books in the Narnia series, published over seven years from 1950. Lewis said he wrote the books he wanted to read.

The stories I loved as a child painted pictures in my mind of other worlds created by the colourful imaginations of their authors. Frances Hodgson Burnet’s The Secret Garden and A Little Princess have made the journey with me from child to adult. What stories to do remember from your childhood are they important to you now?

Having access to books and stories as a child whether they are on the shelves at home or borrowed from a library is a privilege. The stories we hear as children shape our view of the world and expand and enrich the limited experience of home. Stories help children problem-solve real-life situations. Evidence shows children who have fiction read to them regularly find it easier to understand other people – they show more empathy and have a better-developed theory of mind, so, learning the skills of a good doctor starts in childhood.

A childhood without books and stories could be described as an adverse childhood experience.

What is it that makes a story capture the imagination of generations of children and their parents? Maybe it is the ordinariness of the main characters combined with the extraordinary worlds they are transported into. Why are the children in these stories usually the victims of tragedy: war, illness, or bereavement? Is the power because the children in these stories survive and thrive despite their adversity?

Have you handed any of your favourite stories and books on to younger family and friends?

The next time you have the opportunity to spend time with a child, remember the power of stories and see sharing them as gifting a life skill.

On the fourth day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

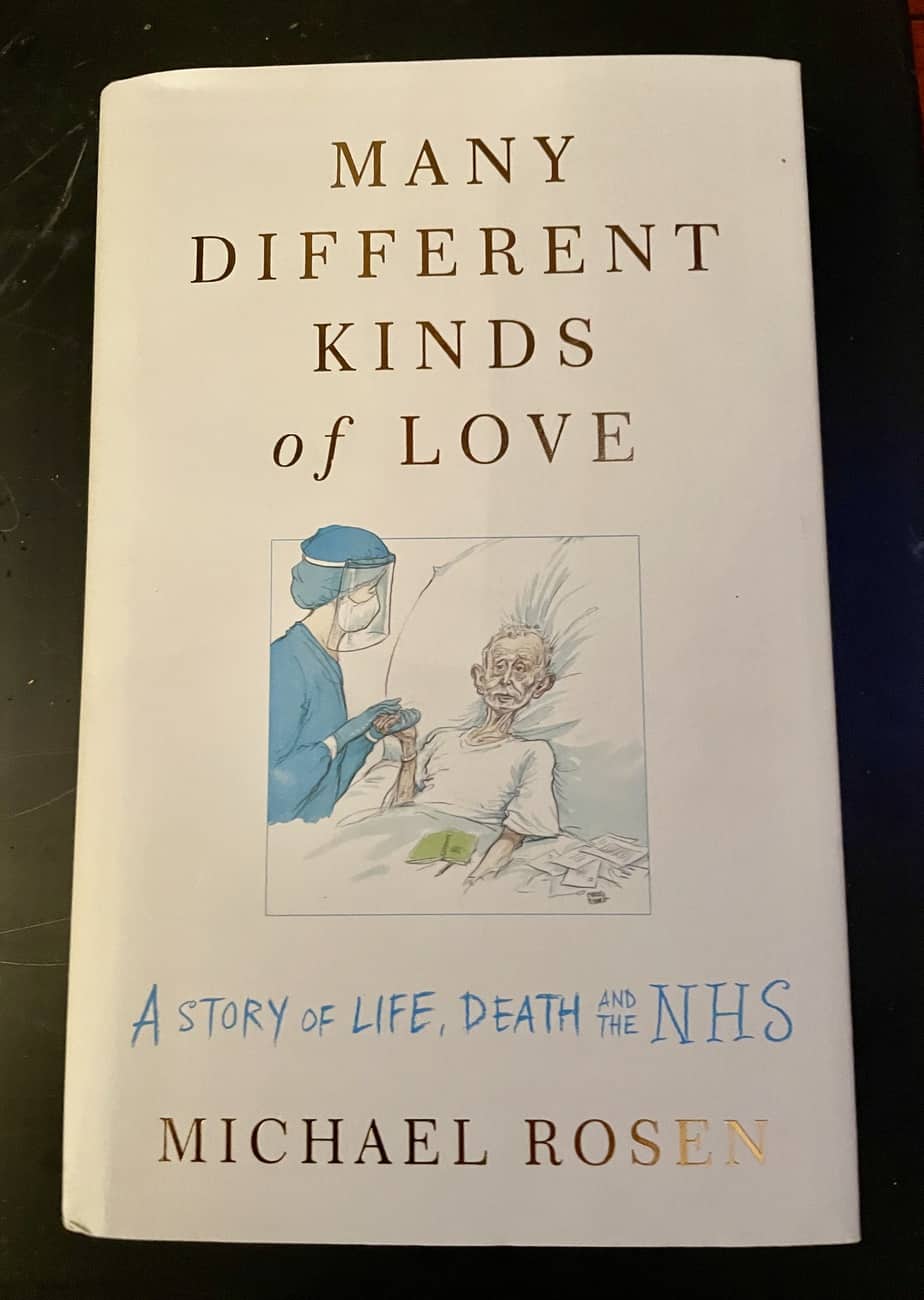

Many Different Kinds of Love, A story of life, death and the NHS, by Michael Rosen

However full your day is of adventure, beauty, joy and kindness it’s difficult to escape completely from the continued presence of Covid. It’s easy for the incredible science of vaccine manufacture to be lost in the pervasive nature of the pandemic, where the uncertainty created by the virus and our political leadership adds to the challenges of daily life. One constant in the chaos has been the care provided to patients by the staff of the NHS. This is captured and shared by Michael Rosen in his reflective poem. He describes his frightening and other world experience of being very poorly with Covid, and his painfully slow recovery which is still ongoing.

His poem is threaded with extracts from the daily diary NHS staff wrote during his stay in ICU, copies of messages from his wife, Emma and illustrations from Chris Riddell. As families were not allowed to visit care diaries provided a record of the life of the patient in ICU. For families whose loved ones died this must have provided some solace to know that behind the PPE real people with hearts and compassion were providing care.

In his poem:

He transmits his fear.

Shares the overwhelming distress caused by the symptoms of Covid.

Conveys the perspective of a patient in the liminal world between life and death.

And during his recovery uses humour and cynicism to convey his frustration with being one of the numbers ill with Covid.

I read the accompanying leaflet:

Possible side effects-

Always diarrhoea

Why isn’t a possible side effect uncontrollable laughter

Or a desire to play the bass guitar?

So much of Michael’s creativity support the staff of the NHS while helping clinicians understand the patients’ experience of illness, demonstrating the role the arts can play in valuing, caring and educating for those who care for us.

On the flysheet in my copy of this book are the words

Each page celebrates the power of community, the importance of kind gestures in dark times, and the indomitable spirits of the people who keep us well.

Easy to see why I have chosen this book for the 4th day of Christmas. I’d encourage NHS staff to read this as a thank you letter and to be part of their commitment to lifelong learning.

Look at last year’s Covid Timeline to read part of the poem.

On the third day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

The Machine Stops, by E M Forster

Imagine sitting at your desk tonight writing a short story that one hundred years from now reflects the lived experience of those alive. That’s exactly what E M Forster achieved with his science fiction short story, The Machine Stops. Writing in 1909 Forster imagined the future and then revealed it to us in his story.

The main character, Vashti lives in an underground pod with all her needs catered for by the Machine.

The clumsy system of public gatherings had long since been abandoned. Instead, communication occurs virtually through the Machine.

…..the round plate that she held in her hands began to glow. A faint blue light shot across it, darkening to purple, and presently she could see the image of her son, who lived on the other side of the earth, and he could see her.

Does this sound familiar?

Even in Forster’s imagined world, he notes that the Machine did not transmit the nuances of expression.

I read this book in the middle of the first lockdown and was amazed by Forster’s description of a Zoom-like technology. The parallels with life during the pandemic were not just the virtual communication but also the isolation and the process of experiences and consumables being bought to people and not vice-versa.

On re-reading the story again this Christmas, there are two other themes that directly relate to our world today. Firstly, the reason why Vashti and fellow her citizens lived in underground pods- the surface of the world was no longer inhabitable (Forster does not mention climate change but it’s hard not to make this association). Secondly – a phrase that stands out as if written in bold,

There will come a generation that is beyond facts

Might we be this generation, where opinions have replaced facts?

It’s Christmas so I won’t be led astray by politics, but do make time to read this short story and reflect on the genius of an author who imagined the future. Penguin publishes the book for just £3, definitely worth the investment, especially as it is accompanied by a magical second short story, The Celestial Omnibus.

On the second day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

Poor, by Caleb Femi

In the UK, the second day of Christmas is known as Boxing Day. Traditionally Christmas Boxes containing goods or money were given to tradesmen and servants to reward them for good work throughout the year. Churches also collected money in boxes to distribute to the poor on Boxing Day. The tradition is mentioned as far back as 1663 in Samuel Pepys’ diary. For most, the tradition has become lost with the passage of time and in 2021 the day is simply an extension to the festivities, time to recover from the excesses Christmas Day or an opportunity to shop.

If the family is in focus on Christmas Day, then maybe Boxing Day should be about looking outwards and learning more about our wider world and the people who are struggling to live in it.

While visiting Edinburgh I came across Typewronger, the smallest bookshop in the city, nestled next to McNaughtan’s (an emporium of secondhand books). Typewronger is beautifully curated with carefully selected books arranged in themes. Books by authors I know and love are displayed next to those unknown to me, yet to be discovered. This style gave me the confidence to pick an unknown book by a known author and to be challenged to choose something different, something I would not normally take home.

Caleb Femi’s collection of poems, prose and photography piqued my curiosity.

Why?

‘To try to understand the experience of another it is necessary to dismantle the world as seen from one’s own place within it and to reassemble it as seen from his.’ John Berger A Seventh Man

Femi is a British- Nigerian whose experience of growing up on the North Peckham Estate, inspired his poems, films and photography. Like Alice Through the Looking Glass Femi’s book has shown me a view of a world I had not before considered carefully enough. As Alice says ‘it’s all rather hard to understand’, and of course it is. Until you have experienced poverty, hunger, discrimination, fear, how can you really understand?

When you get tired of running from danger

you become the danger

Femi’s book does exactly what it should do; it makes you stop, and think and try to understand. I know more now than I did before thank you @Calebfemi_

The perfect Boxing Day book and a great resource for teaching about compassion and understanding.

On the first day of Christmas, the book shop sent to me

The Christmas Mystery by Jostein Gaarder

Any book that starts its story in a dusty corner of an old book shop wins my heart. This classic Christmas novel has been a companion for over 25 Christmases. Christmas is all about stories, creating a rich tapestry woven of religious beliefs, pagan festivity, cultural celebrations and the new threads we add each year from the stories and rituals we create with family and friends. Jostein Gaarder’s story captures the essence of Christmas, it transcends beliefs and the boundaries of nations and time. It is a story for both children and adults. Often described as fantasy, it feels more like magical realism with the fantastical philosophical touch common to all Gaarder’s books. In the story, a young boy, Joachim unravels the mystery of Elizabet’s disappearance in time and space. Like Advent, the story is divided into 24 chapters, which makes it a wonderful accompaniment to the daily opening of an advent calendar window. Why not buy yourself an early Christmas present for next year so it’s ready to start reading on the 1st December 2022 with your first mince pie.