Just to warn you, there are a lot of words and thoughts on this page before you get to the art.

Doctors aspire to offer patients ‘compassionate care’ but do we have a shared understanding of what this means and how it can be delivered consistently in the NHS?

Defining Compassionate Care

Defining the words, ‘sympathy’, ‘empathy’ and ‘compassion’ is complex.

These are the definitions on which I base my teaching:

Sympathy is thinking and feeling what your emotions might be if you were in the position of another person.

It is about you and not the other person.

Empathy is thinking and feeling what another person’s emotions are in their situation.

It is still about you; empathy alone does not help the other person.

Compassion is the ability to be empathic and be motivated to do something to help another person. Compassion provides the link between understanding and caring. It involves feeling for and not feeling with another.

It is about the other person and you.

Compassionate care involves offering ‘person-centred care’. It can be described as the art of attentively listening to the patient and connecting with them in a way that forms a healing relationship where wellbeing, trust, treatment and compliance are facilitated.1It is about the human and not the purely scientific dimension of care. The essence of patient care is caring for the patient. 2

Why is compassionate care important?

Compassionate care benefits both patients and medical staff. It improves patient outcomes and illness experience and increases patient satisfaction and compliance. It reduces patient anxiety and complaints.3 Practising compassionate care is linked with higher levels of job satisfaction and wellbeing.4 Studies show that doctors who are unable to work in a culture where they show empathy and offer compassionate care are at higher risk of stress, burnout, and substance abuse.5

Doctors can only offer compassionate care if they are treated compassionately by their colleagues, employers, and regulators. 3

In 2010 the UK government legislated that NHS staff should offer compassionate care. 6It might be assumed that doctors, being human should naturally provide compassionate care. Despite this recommendation and assumption many recent high-profile cases in the UK have highlighted care that lacked compassion. 7 In its report Behind Closed Doors,8The Point of Care Foundation argues that ‘the hard truths learned through the Francis Inquiry are in danger of being forgotten in the light of unprecedented, continuing, and seemingly endless service pressures.’ The Foundation recommends that all organisations should prioritise the care of their staff and act on the knowledge that the way staff feel at work affects the way they care for patients.

‘Compassionate care should not be an optional extra’.9 Currently there is no open and honest debate about the barriers to offering compassionate care, and it is not routinely defined, discussed, prioritised, valued and cultivated. A change in culture is required to bring more compassion to the heart of NHS care.

There is scope for more openness and discussion about doctors’ relationships with their colleagues and other NHS staff. Doctors, their teams, organisations and government do not consistently and routinely prioritise and value compassionate care of patients and colleagues. It should be valued as a skill, routinely discussed over coffee, in team meetings, in tutorials, by clinical supervisors and at appraisal. This issue is discussed in Caroline Elton’s compelling book ‘Also Human- The Inner Lives of Doctors’. 10 Elton, a psychologist, explores her work with junior doctors and highlights the importance of doctors being compassionate and being shown compassion by managers, colleagues and patients.

It is very easy to blame the NHS cultural system, but the system is made up of individuals and as Haslam says if every single person involved in healthcare from governments all the way through to front line staff understands the importance of compassionate care and behaves as if they believe in its value then the system will change, and patient care will improve.9

What are the barriers to providing compassionate care?

- Having a medical education system that is based on learning facts about disease rather than learning how to understand people’s experience of illness.

- Being asked to offer task-based care rather than person-centred care.

- Working in a rapid access service rather than one based on continuity of care.

- Regulation that evaluates process and protocol rather than outcomes based on values such as compassion.

- The erosion of hospital ‘firms’ which results in a ‘collusion of anonymity’ where many members of the team see a single patient, but no one takes overall responsibility for the patient’s care- a concept first described by Michel Balint 11

- A lack of role models seen to be offering compassionate care. This is particularly important for medical students and doctors in training.

- Working in an organisation whose culture does not value and offer compassionate care to patients and staff.

- Fear of compassion fatigue and a failure to recognise the limits to empathy.

How can compassion be cultivated?

It can be difficult to discuss the concept of compassionate care as a whole, but all doctors can recognise, be shown and be taught the individual attributes that combined together to facilitate compassion.

The attributes that build compassion include:

- Valuing the patient.

- Connecting with the patient through attentive listening

- Being curious about the patient’s life; suspending judgement and allowing uncertainty

- Treating the patient with good manners, dignity, and kindness

- Acting in a reassuring and honest manner that promotes trust

- Showing respect for the patient’s views and acknowledging that the patient’s perspective is their truth

- Recognising the patient’s emotion

- Understanding that the ‘laying on of hands’ in examining a patient plays a significant role in establishing trust and aiding healing

- Recognising and feeling the privilege of caring for patients

- Reciprocal altruism; where the doctor provides compassionate care but is also shown compassion from patients and colleagues and the system in which they work

I’ve used the term patient in this list but the word ‘other person’ can be used with equal effect.

Compassion cannot be learnt in a lecture theatre as part of a taught curriculum. In medical school and speciality training it is usually developed from watching the behaviour of colleagues and supervisors in the ‘hidden curriculum’ of teaching that occurs in the GP surgery, at the patient’s bedside and in the hospital corridors. The individual attributes of compassion can be cultivated and nurtured by personal study, small group learning, role play, mentoring, and appraisal; using guidance from research, written resources, expert patients and the creative arts. Practising compassionate care is about developing a different mindset that has to be practised and developed with guidance and appropriate feedback. There is a role for personal study, small group learning, role play, mentoring and appraisal using evidence and guidance from research, written resources, expert patients and the creative arts.

Clinical supervisors often criticise doctors in training for learning empathic statements by rote and including these when talking with patients. But this can improve connectedness with the patient, is an important step in learning empathy and may with time lead to the doctor developing a real understanding of compassionate care.

Compassion grows from empathy. Find out more about empathy and sympathy by watching BrenéBrown’s RSA short animated film on YouTube.

Empathy can be measured, Professor Simon Baron-Cohen and his team have developed an online empathy test.

Empathy can be taught and developed. There are research and discussion articles outlining the psychological and neurophysiological processes that support this statement.12

Trainees in General practice are recruited for their ability to demonstrate empathy. Empathy and the attributes that enable compassionate care form the core of their training and are regularly assessed.

Training for compassion using meditation-related techniques, the most common being ‘loving-kindness training’ has been shown to improve feelings of wellbeing and feelings of compassion towards others. 13Trainees on the York GP Training Scheme visited a local meditation centre to learn about meditation and experience a ‘loving-kindness mediation’. Evaluation of the session in terms of personal gain and learning skills to help patients was very positive.

Empathy is not a simple or single construct. In the book ‘Empathy’ Goleman describes three distinct types of empathy.14

- Cognitive empathy- understanding another’s perspective

- Emotional empathy- Feeling what someone else feels

- Empathic concern- sensing what another needs from you

Empathic concern is governed by a neural response.12 When we see someone suffering, the amygdala responds by labelling this experience a threat, and the prefrontal cortex releases oxytocin; the ‘care chemical’. We feel the patient’s pain and then consciously decide how we respond to feeling the patient’s distress. The process of caring requires a doctor to manage their own feelings. If the feelings of sympathy become overwhelming or unchecked an individual can develop compassion fatigue. There are many situations where choosing to be detached from the situation allows a doctor to offer appropriate care and is an appropriate act of self-preservation. Most of the time patient care is dependent on it arising from empathic concern. I’ve observed that doctors often try to find a balance between empathic and detached concern, and frequently equate detached concern with being professional.15 Neighbour argues that there is no midway position; the art of compassionate care involves knowing when to engage or disengage empathy according to clinical circumstances.16 It is this skill that will protect doctors against compassion fatigue.

Compassion is not time-consuming nor does it rely on being an expert, it can be shown through small acts of kindness such as the touch of a hand, the passing of a tissue, or a smile in the corridor. A simple introduction, ‘hello my name is’ as Dr Kate Granger highlighted can make all the difference. It is in the detail of the care not the broad brushstrokes of the science.

To summarise, any doctor wishing to develop their compassionate care should aim to:

- Work towards collaborative solutions that benefit everyone. (no winners and losers)

- Take regular breaks that are focused on their own needs.

- Share responsibility, so they don’t feel they are the only one that can help.

- Develop emotional intelligence to help them distinguish the right time to engage and disengage their empathy muscle.

What role do the arts play in the cultivation of compassion?

‘Art moves the soul, we weep with the weeping, laugh with the laughing, grieve with the grieving’.

Alberti ‘On Painting’ 1435

The word empathy has arisen from the German word ‘Einfühlung’ which describes an emotional knowing of a work of art from within by feeling an emotional resonance with the art. The German word was introduced to the medical vocabulary in the 19thcentury by Lipp, a psychologist who used the word to mean ‘feeling one’s way into the experience of another’. He describes how empathy can be elicited by the inner imitation of the actions of others. 12

Many doctors and artists use art as a metaphor to convey the meaning of compassion. In 1927 Dr Francis Peabody, doctor, educator, and humanist, wrote, ‘What is spoken of as a ‘clinical picture’ is not just a photography of a man sick in bed; it is an impressionistic painting of the patient surrounded by his home, his work, his relations, his friends, his joys, sorrows, hopes and fears’.2

To be empathic you need the ability to imagine another’s experience. The broader a doctor’s repertoire of imagined experience the better able they are to understand their patient’s experience and offer compassionate care. The depictions of the lives of others in the creative arts and humanities can help broaden and build this repertoire. There is evidence to support a positive correlation between exposure to the arts as a medical student and the ability to show empathy and there is a negative correlation with symptoms of burnout.17 More research needs to be undertaken to prove a causal relationship in medical students and doctors.

The arts can also provide a stimulus for doctors to share experiences and talk about how they provide care. The resources on this page are intended to do just this.

pictures to prompt thought and discussion about compassion

Presented to The Tate by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Fildes son, Phillip, died from typhoid fever on Christmas morning 1877. The painting was commissioned in 1890 by Henry Tate as a work of ‘social realism’. It is said to have been inspired by the compassionate care Dr Murray gave to Filde’s son and family. Fildes wanted “to put on record the status of the doctor in our time”. It has originally displayed in the Tate in London, where it can still be seen today. It is probably one of the most famous pictures of a doctor in Western Art.

Asking doctors to describe what they see in the picture is usually enough of a prompt for a useful discussion about compassionate care, the role of the doctor and the consultation.

Picture in the public domain

Francisco Goya 1820

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The inscription along the bottom of the painting reads, ‘Goya, in gratitude to his friend Arrieta: for the compassion and care with which he saved his life during the acute and dangerous illness he suffered towards the end of the year 1819 in his 73rdyear. He painted this in 1820. ‘

What does this painting show and why you think Goya painted it?

Picture in the public domain

Contrast this picture with Goya’s earlier work from 1797-99; an etching ‘Capricho 40, Of what illness will he die?’

This is a picture by Magritte, it can be viewed on-line in the book ‘Rene Magritte’ by James Thrall Soby published in 1965, now out of print.

In the painting a stone man is gently taking out a speck of dirt from another stone man’s eye. An interpretation of the picture is that Magritte has shown that living men can turn to stone and be unfeeling but they can soften and show compassion through a simple act of kindness.

The story of the ‘Good Samaritan’ from Christian teaching is an archetypal example of compassion being shown to a stranger.

Are there stories you know from childhood or other world religions that depict compassion?

Picture in the public domain

The Touch of Comfort Camel Cauchi 1994

Take a look at this picture by Carmel Cauchi on Art UK website

Comforting another person in distress with a hug is a powerful way of demonstrating compassion. Touching patients to examine them is part of the routine care doctors provide, in what way to do doctors demonstrate compassion, is it ever with a hug?

books to prompt thought and discussion about compassion

There are many books written about how to cultivate compassionate care. The book ‘Empathy’ by Daniel Goleman, Annie Mckee, Adam Waytz is published as part of the HBR Emotional Intelligence Series. It is a good starting point to explore more about empathy. The book explores the challenges of understanding empathy and how empathy can lead to compassion. It signposts to other resources for further reading.

Against Empathy- The Case for Rational CompassionPaul Bloom published by Bodley Head.

The Empathy Instinct Peter Bazalgette Published by John Murray

These two books published in 2017 take a fresh look at empathy and

highlight the confusion that surrounds its meaning and its usefulness in creating a more caring society. Bloom argues that empathy alone is not enough, and it is rational compassion that has the capacity to change the world for the better. Sally Vicker’s review of these books published in the Guardian might prompt an interesting tutorial discussion.

Death of Ivan Ilych Leo Tolstoy (1886) Published in translation in the UK by Penguin

The picture on the front of this penguin edition is ‘The Convalescent’ by Carolus-Duran 1860 Musee d’Orsay.

This is one of Tolstoy’s most acclaimed short stories. The story tells of the decline in Ivan Ilych’s health and his eventual death. Ilych recognises he is dying and begins to reflect on his life. He is tortured not only by his physical pain, but by his mental anguish as he starts to regret many of the choices he has made. The only character in the story who is able to offer understanding and compassion is Grasim, the young peasant who waits on his table.

‘Without a single soul to understand or care for him,’Tolstoy describes how helpless Ilych feels.

This story covers important issues; the illness experience, death, dying and palliative care. It should help doctors understand the overriding importance of compassionate care.

How Much Pain Is Too Much Pain Hilary Mantel

This short story discusses the author’s experience of chronic pain.

This is her description of compassionate care:

‘A few years ago, when the pattern of pain had become more insistent and less easily managed, I was referred to a neurologist. My hour with him stays with me as a shining example of good practice. His history-taking was so structured, so searching, so thorough that I felt that, for the first time my pain was being listened to. The consultation was itself therapeutic.’

Sometimes reading the review of a book can be enough to stimulate discussion and broaden perspectives. Here are two examples of reviews that do just that.

The Lost Art of Healing Bernard Lown (1996) Published by Houghton Mifflin

Reviewed in The BMJ Book Review 1997

‘Dr. Lown explains, the art of healing does not mean abandoning the advances of modern science, but incorporating them into a sensitive, humane, enlightened approach to medical care.’

Medicine in its Human Setting A. E. Clarke-Kennedy (1954) Published by Faber and Faber

Reviewed by A MacNalty in the BMJ Book Review 1955

This is a book of 22 medical short stories. Clarke-Kennedy’s aim in writing the stories was to ‘correct the bad habit of thinking of diseases as if they had a real existence apart from the men, women and children who suffer them: and to impress the lesson that the real object of medicine is not the application of science to a diseased body but the relief of human suffering.’

The Water Babies Charles Kingsley 1863 First published as a serial for Macmillan’s Magazine

One of my memories from childhood is reading Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies. In this Victorian children’s story, I recall being introduced the character of Mrs Doasyouwouldbedoneby. (Mrs D) In the story this lady and her contemporary Mrs Doasyoudid act as moral guides to Tom, a young chimney sweep who is transformed into a water baby. Mrs D shaped my thinking and influenced my early medical practice (until, I began to entertain the possibility that not every patient I saw might want to be treated exactly as I would like to be treated). This change in perspective occurred through talking to patients, reading and having my medical skills nurtured by inspiring GP Trainers.

It’s important to have positive role models. Whose might yours be?

The moral code of Kingsley’s fictitious character is clearly based on the philosophy of others, known as the ethics of reciprocity.

The year after The Water Babies was published Parliament began the reform process that led to the 1864 Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act, which helped liberate countless children from unimaginable suffering, demonstrating the power of literature to change lives.

Many children’s stories contain examples of compassion, can you think of an example? Perhaps one you read as child or one you are reading now to your children.

A Christmas Carol Charles Dickens 1843 Published by Chapman and Hall

This well-known Christmas story is a classic tale of kindness and compassion triumphing over greed and selfishness. Scrooge, renowned for his thoughtless and unkind practices undergoes a transformation on Christmas Eve at the hands of a ghost who encourages him to see the error of his ways. Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning a changed man, sees the joy in giving and from then on treats everyone with kindness, generosity and compassion, embodying the spirit of Christmas.

It’s interesting to think about what motivated Scrooge to change, and to consider why individuals in society today have not learnt from his transformation.

poetry to prompt thought and discussion about compassion

Her Long Illness Donald Hall

Daybreak until nightfall,

he sat by his wife at the hospital

while chemotherapy dripped

through the catheter into her heart.

He drank coffee and read

the Globe. He paced; he worked

on poems; he rubbed her back

and read aloud. Overcome with dread,

they wept and affirmed

their love for each other, witlessly,

over and over again.

When it snowed one morning Jane gazed

at the darkness blurred

with flakes. They pushed the IV pump

which she called Igor

slowly past the nurses’ pods, as far

as the outside door

so that she could smell the snowy air.

Ye Wearie Wayfayer Adam Lindsay Gordon 1866

Gordon was an Australian Poet, and rather bizarrely also a jockey and politician.

This is the ending of one of his ballads:

‘Question not, but live and labour

‘Til yon goal be won,

Helping every feeble neighbour,

Seeking help from none;

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.

The origin of this next poem is uncertain. General consensus is that when an old lady died in the geriatric ward of a hospital, it appeared she had left nothing of value but on packing up her possessions, a nurse found this poem.

See Me

What do you see Carers, what do you see?

What are you thinking when you look at me?

A crabbit old woman, not very wise

Uncertain of habit, with far away eyes.

Who dribbles her food and makes no reply

When you say in a loud voice “I do wish you would try”

Who seems not to notice the things that you do

And forever is losing a stocking or shoe

Who, unresisting or not, lets you do as you will

with bathing and feeding the long day to fill

Is that what you’re thinking, is that what you see?

Then open your eyes, you are not looking at ME.

I’ll tell you who I am as I sit here so still

As I move at your bidding, as I eat at your will.

I’m a small child of ten with a father and mother,

brothers and sisters who love one another.

A young girl at sixteen with wings on her feet

dreaming of soon now a lover she’ll meet.

A bride soon at twenty – my heart gives a leap

remembering the vows that I promised to keep.

At twenty-five now I have young of my own

who need me to build a secure happy home.

A woman of thirty my young grow fast

bound to each other with ties that should last.

At forty, my young now soon will be gone but my man stays beside

me to see I don’t mourn.

At fifty once more babies play round my knee

again we know children, my loved one and me.

Dark days are upon me, my husband is dead

I look at the future, I shudder with dread.

For my young are all busy rearing young of their own

and I think of the years and the love I have known.

I’m an old woman now and nature is cruel, ’tis her jest to make old

age look like a fool.

The body it crumbles, grace and vigour depart

and now there’s a stone where I once had a heart.

But, inside this old carcass, a young girl still dwells

and now and again my battered heart swells.

I remember the joys, I remember the pain, and I’m loving and living

life over again.

I think of the years all too few – gone so fast

and accept the stark fact that nothing can last.

So open your eyes, Carers, open and see

not a crabbit old woman, look closer – see ME.

Prayer before Birth Louis MacNeice

e.e. cummings

This quote from e.e. cummings reminds us that compassionate care of another depends on being able to value and respect yourself:

‘We do not believe in ourselves until someone reveals

that deep inside us something is valuable,

worth listening to, worthy of our trust, sacred to our touch.

Once we believe in ourselves, we can risk curiosity, wonder,

spontaneous delight or any experience that reveals the human spirit.’

music to prompt thought and discussion about compassion

Music has the potential to evoke powerful emotions.

It’s often very personal.

These are some suggestions made at a recent Seminar where GPs were ask to suggest a piece of art that helped them understand compassion.

‘Symphony number 3 Pastoral’ Vaughan Williams

‘Spiegel Im Spiegel’ Arvo Part

‘A case of you’ Joni Mitchell

‘I was not expecting that’ Jamie Lawson

What would you chose?

film to prompt thought and discussion about compassion

The Evening Thread by Iris Moore a short stop-motion film made entirely by hand with watercolour and paper cut-outs.In the film, an old woman prepares to die. Accompanied by her granddaughter, she reflects on the memories of her life, and on the profound experience of being human, before taking the next step into the unknown.

further inspiration to prompt thought and discussion about compassion

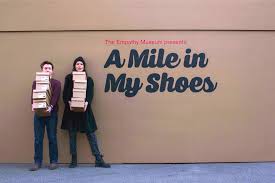

A Mile in My Shoes

A Mile in My Shoes

‘The biggest deficit that we have in our society and in the world right now is an empathy deficit. We are in great need of people being able to stand in somebody else’s shoes and see the world through their eyes.’ Barack Obama

A Mile in My Shoes was an art project in a shoe shop where visitors were invited to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes – literally. Housed in a giant shoebox, this roaming exhibit held a diverse collection of shoes and audio stories that explored our shared humanity. From a Syrian refugee to a sex worker, a war veteran to a neurosurgeon, visitors were invited to walk a mile in the shoes of a stranger while listening to their story. The stories covered different aspects of life, from loss and grief to hope and love and took the visitor on an empathetic as well as a physical journey.

Quotes

‘If you want others to be happy, practise compassion. If you want to be happy, practise compassion.’ The Dalai Lama

‘I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will not forget how you made them feel.’ Maya Angelou

‘One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient’. Dr Francis Peabody

Is there a quote that helps you practise compassionate care?

Medical Oaths

In California, Professor Rachel Remen runs a medical school course called ‘The Healer’s Art,’ in which students learn how to offer stronger emotional support to their patients, their colleagues, and themselves. As part of the class, she and other students wrote their own versions of the Hippocratic oath

This is an example of an oath one of the students wrote:

‘Do not ask me what is wrong, for I may not know. Do not ask me why this happened, for I may not know. Do not ask me what to do, for I may not know. But ask me if I will try to understand, if I will think of you first, if I will stay with you, and I may be able, at last, to lift my eyes to meet yours, and say, “Yes, yes, yes, I will.’

What might your medical oath be?

references

- Lown B. The Lost Art of Healing: Practicing Compassion in Medicine. New York: Ballantine Books, 1996.

- Peabody F. The Care of the Patient. The Journal of the American Medical Association. March 19, 1927 Vol 88, No. 12

- The Point of Care Foundation

- Kearney M, et al, Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: ‘being connected… a key to survival’ 2009 JAMA 301 (11) 1155-1164

- Zuger, A. Dissatisfaction with Medical Practice. New England Journal of Medicine. 350, 2004: 69-75.

- Policy Paper 2010 to 2015 Government Policy: Compassionate Care in the NHS. Updated 8 May 2015

- Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry: executive summary, 2013

- Cornwell J, Fitzsimons B. Behind Closed Doors. 21 July 2017. The Point of Care Foundation

- Haslam D. More than Kindness. Journal of Compassionate Health Care20152:6

- Elton C. Also Human, The Inner Lives of Doctors. William Heinemann, 2018

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Oxford: International University Press, 1957

- Riess H. The Science of Empathy. Journal of Patient Experience

2017, Vol. 4(2) 74-77 - Fredrickson B. Cohn M, Coffey K, Pek J, Finkel S. Open Hearts Builds Lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness mediation. J Pers.soc. Psychology 2008 95, 1045-1062

- Goleman D, Mckee A, Waytz A. Empathy. HBR Emotional Intelligence Series. 2017

- Jeffrey D.Clarifying Empathy: the first step to more humane clinical care. Br J Gen Pract2016; 66 (643): e143-e145.

- Neighbour R. Detachment and Empathy Br J General Practice 2016:66 (650) 460

- Magione S. Medical Students’ Exposure to the Humanities Correlates with Positive Personal Qualities and Reduced Burnout: A Multi-Institutional U.S. Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine May 2018, Volume 33, Issue 5 PP 628-634

Updated 5th April 2021