Medical ThemeIllness

introductionHow do you define illness?

The thesaurus suggests that other words like disease, condition, ailment and incident can be used interchangeably with the word illness. However, I think that illness is a unique concept that results from the impact of a disease or condition on an individual. For example, tonsillitis is a disease or condition, but illness is the lived experience of the person suffering from tonsillitis.

You could define illness as:

Something that interferes with your sense of wellbeing

A loss of function

Suffering

The restriction of options or possibility

A state of inability

A label given by doctors or society

Limitations on quality and quantity of life

A loss of control of biological, psychological, or social functioning

What words or phrases might you use?

Illness might be described the loss of harmony between the biological body and the lived experience of it.

Susan Sontag’s use of metaphor helps us understand the experience illness.

Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship.

Everyone who is born holds duel ownership, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.

Although we prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor

Key insightsOver 40% of the UK adult population live with a longterm health condition.

Illness can be described the loss of harmony between the biological body and the lived experience of it.

‘It is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has’ William Osler

General OverviewAs clinicians we care for a person, not just treat a disease.

We can’t provide compassionate care if we don’t understand the patient’s perspective.

It was only in 1977, that George Engel proposed a new model for medicine that encompassed the patient’s perspective- the ‘biopsychosocial model’. I remember the novelty of this approach being discussed in my undergraduate medical education.

Listening to the patient and allowing time to hear their story is the best way to learn. Expert patients are often involved in teaching sessions to help learners explore the effect of a particular illness. This is not always practical or easy to arrange, so art that has been created by people with ill health, to communicate their experience and suffering has a valuable role to play in helping clinicians explore the patient’s perspective.

I have found Havi Carvel’s book on illness a helpful guide to understanding the patient’s perspective. Her framework for explaining and understanding illness is a useful teaching tool and a good starting point for this webpage of resources.

But, before we move on, it’s not possible to explore the concept of illness without first defining health.

What is health?

This is a good question for a tutorial.

The concept of health is also difficult to define. You maybe familiar with the WHO definition, but in a world where the majority of illness and suffering is not curable or solvable, aspiring to make everyone healthy can’t be a realistic aim.

This metaphor helped me understand what health is.

If we are fish then is health is the water we swim in, we don’t notice it until it disappears.

Using Art to explain illnessIllness can be explained and understood from these three perspectives:

The naturalistic approach

The normative approach

The phenomenological approach

Combining all three approaches provides a comprehensive view of illness to enable you to help your patient.

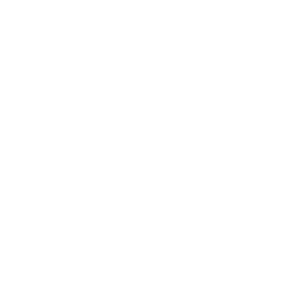

The Microscopic Anatomy of the Human Body in Health and Disease, Arthur Hill Hassall (Wellcome Collection)

The Naturalistic Approach

The naturalistic approach explains illness as biological dysfunction in terms of physical facts e.g. changes in a cell noted under a microscope, or the presence of bacteria in the urine.

The effect of an illness will be universal when all other variables are the same.

This view had resulted in incredible advances in treatment but excludes the ill person’s perspective.

There are many ways in which art can be used in medical education to help us understand normal anatomy and how it changes with disease.

What is this a picture of?

Understanding what happens to the normal body when it is effected by disease and disability is an essential part of medical education.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, Anne Fadiman

The Normative Approach

The normative approach explains illness through the collective lens of culture and society.

Whilst it’s helpful to have the societal context of illness it also excludes the personal perspective and can result in stigma.

Anne Fadiman’s book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, is an account of the conflict between clinicians in an American Hospital and the family of a Hmong child from Laos. The child suffered from epilepsy, in the eyes of the clinicians this was a disease that needed treating with regylar medication but the family believed the fits were a gift from their gods; the spirit catches her, and she falls down, that should not be prevented.

Who is right? How should this child be cared for?

Can you think of other illnesses that are viewed in different ways by different cultures?

Illness can also be stigmatising leading to misunderstanding and isolation.

These two resources help explore the stigma associated with certain illness.

C4’s It’s A Sin by Russell T Davies follows the story of a group of friends whose lives were impacted by AIDS.

The Island by Victoria Hislop tells the story of islanders infected with Leprosy. Before the advent of antibiotics people who became infected were banished to a neighbouring island to live in isolation

Stolen Moments, When Skies are Gray, Shanali Perera

The Phenomenological Approach

The phenomenological approach explains illness through the lived experience of the person who is ill.

The art of patient care is to explore the patient’s understanding and experience. In clinical care this is often distilled into a series of questions focused on establishing I.C.E. (the patient’s ideas, concerns and expectations) For the patient to feel seen, heard and cared for it’s essential to take time to listen to and explore the patient’s story.

Shanali Perera’s life as a junior doctor changed path when she developed a rheumatological condition. She took up digital art to help her make sense of her experience. She ask herself the question what does my lived experience of illness look like?

I was introduced to Shanali’s work at the Creative Health for Wellbeing Alliance’s conference where she spoke about her experience of illness, do take a look at her website.

Supervisor Sleeping, Lucien Freud, 1995

Who decides what is an illness?

Societal health beliefs evolve over time and are not always linked to new scientific knowledge. Since first writing this page celebrity opinion expressed through social media has become a powerful influence on how individuals and societies perceive illness.

How has society’s perspective of mental illness changed over the years?

Reflect on this painting by Lucien Freud.

Being overweight can cause ill health - is it an illness?

Who decides what an illness is?

Science or society?

Sebastian Barry’s book The Secret Scripture tells the story of Roseanne McNulty who was committed to a psychiatric hospital as a young adult purely because she conceived a child out of wedlock. Her behaviour was labeled as an illness.

Art Resources to understand illnessArt offers a way to express and explore the experience of illness. These works invite reflection, discussion, and new perspectives on what it means to experience ill health.

Why not include art in your teaching.

Any of these pieces of art and associated text could be used as a catalyst for learning with students or doctors in training.

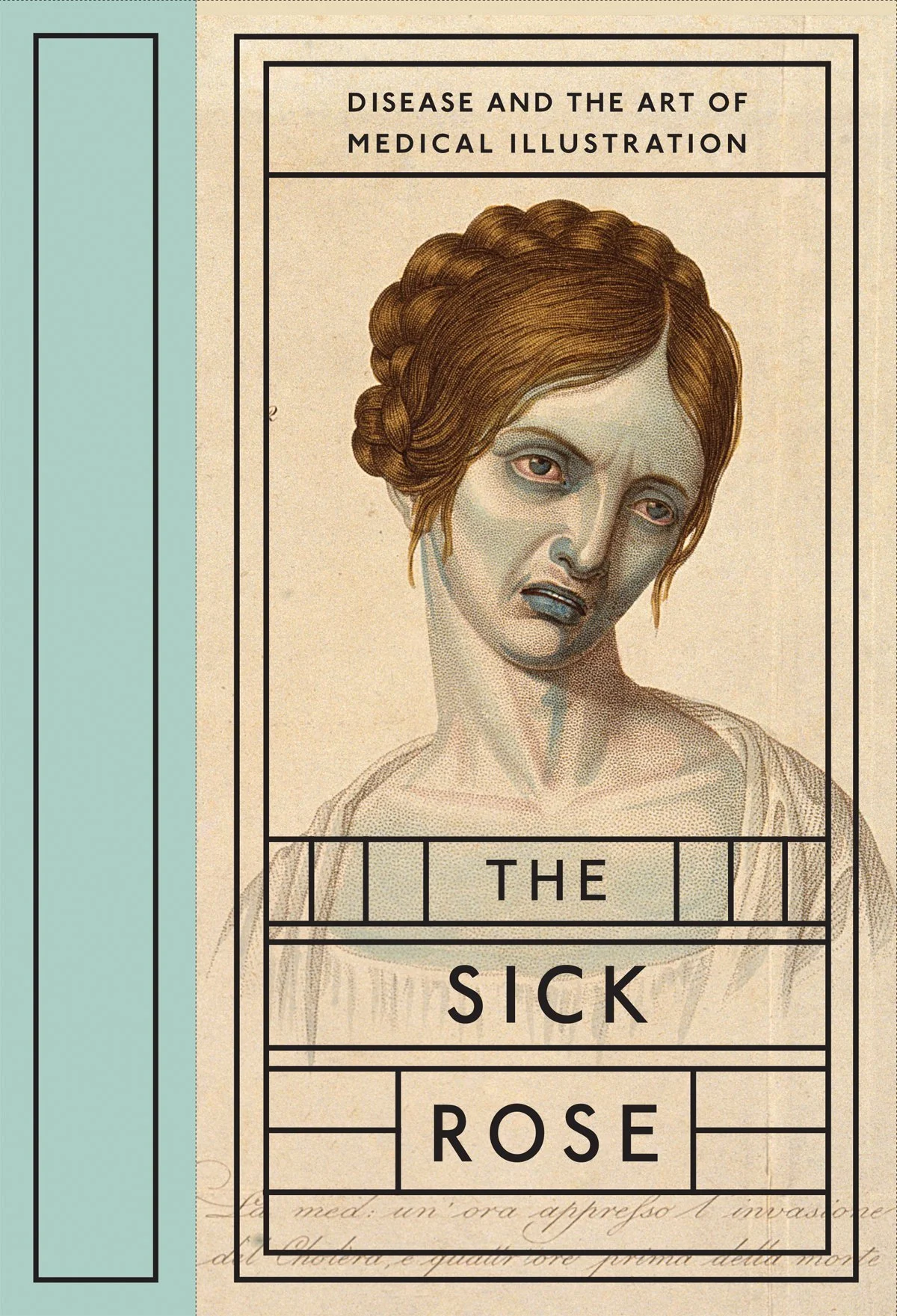

The Sick Rose, Wellcome Collection.

What does illness look like?

What is it about a patient’s appearance that communicates they are suffering from an illness?

This etching is of a young woman from Vienna who died of cholera. She is depicted when healthy and then four hours before death.

Is illness always visible?

What picture would you choose (or is there a poem, song or piece of music) that conveys the concept of illness to you?

Doctors are trained to recognise illness. We listen to the patient’s story, assess their signs and symptoms and often arrange and review investigations before we confirm an illness.

How does a person convey their ill health to other people, especially if there are no visible signs of illness?

The Heart Attack, Glen Colquhoun

What causes illness?

Take a few minutes to reflect on this poem by New Zealand doctor and poet, Glen Colquhoun. It’s taken from his anthology of poems for doctors (a great teaching resource).

I hope Glen is happy for me to reproduce his poem to use in your teaching, maybe it will encourage you to buy his anthology.

The Heart Attack

The heart is not attacked

by red Indians clinging underneath

the bellies of their ponies.

The heart is not attacked by

kamikaze flying their exploding planes

onto its burning decks.

The heart is not broken by the slippery hands of love.

The heart is not squeezed like

ripe lemons into a clean glass.

The heart is not beaten by

arrangements of its soft belly

around a hard fist like a glove.

The heart is not stabbed by bayonets

or chainsaws or carefully sharpened kitchen knives

slipping their cold steel cleanly between its ribs.

The heart stops simply like a blocked toilet

While someone unsuspecting is opening the

newspaper or reading poetry or staring quietly at

the pictures in the calendar on the back of the door.

Sunday seems a good day for fishing.

A pair of trousers fall to the floor.

If you write a list of causes of illness what would be on it?

What about the expression ‘he died from a broken heart’?

Can emotions cause illness?

The influence of culture, family, and life experience needs to be appreciated when exploring illness and health beliefs.

There may be stories you were told as a child about illness that influenced your behaviour. One of my children was told by a friend’s mum that sitting on cold floors gave you piles!

Can you recall any explanations for illness from your childhood that you know now are not true?

In the UK there are examples where people have been classified as suffering from an illness purely because their behaviour does not conform to what contemporary society expects.

Can you think of any examples?

What about illness that does not yet have a scientific explanation?

Susanne O’Sullivan, consultant neurologist is an expert in functional illness. Her book is a collection of stories from around the world about illness that defies a conventional scientific explanation. In a world where what we see down a microscope or read reported in terms of millimoles per litre shapes our understanding of illness, O’Sullivan reminds us that events in our communities and our cultural beliefs also have the potential to shape our health and wellbeing. The book is also an interesting read for non-medics as it explores many topical health stories, such as the Havanah Syndrome in Cuba. It’s an essential read for any clinician or medical student as the concept of functional illness does not fit neatly with the dogma of western medicine, is often excluded by clinicians from the differential diagnosis and is rarely accepted by patients. It is an easy read and a great resource for a tutorial or teaching session.

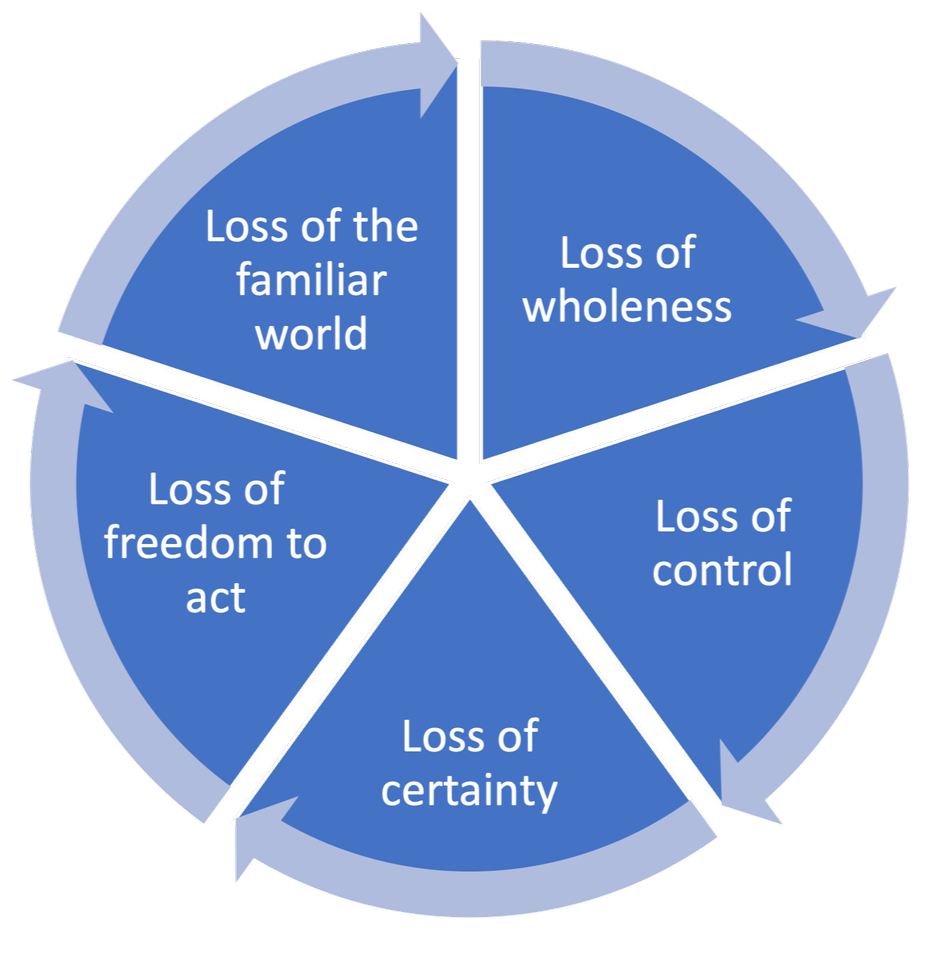

Five Essential Features of Illness.

The impact of illness

The experience of illness is so much more than the physical and mental symptoms, and is frequently associated with loss, as described by Toomb’s and shown in this infographic, ‘Five essential features of illness’ .

Other pages of the website will explore in more detail how we cope with illness.

Art Resources To explore the patient's perspectiveAll these resources have been used in teaching and provoked discussion and learning about the patient’s perspective. Why not try them out in your learning/teaching?

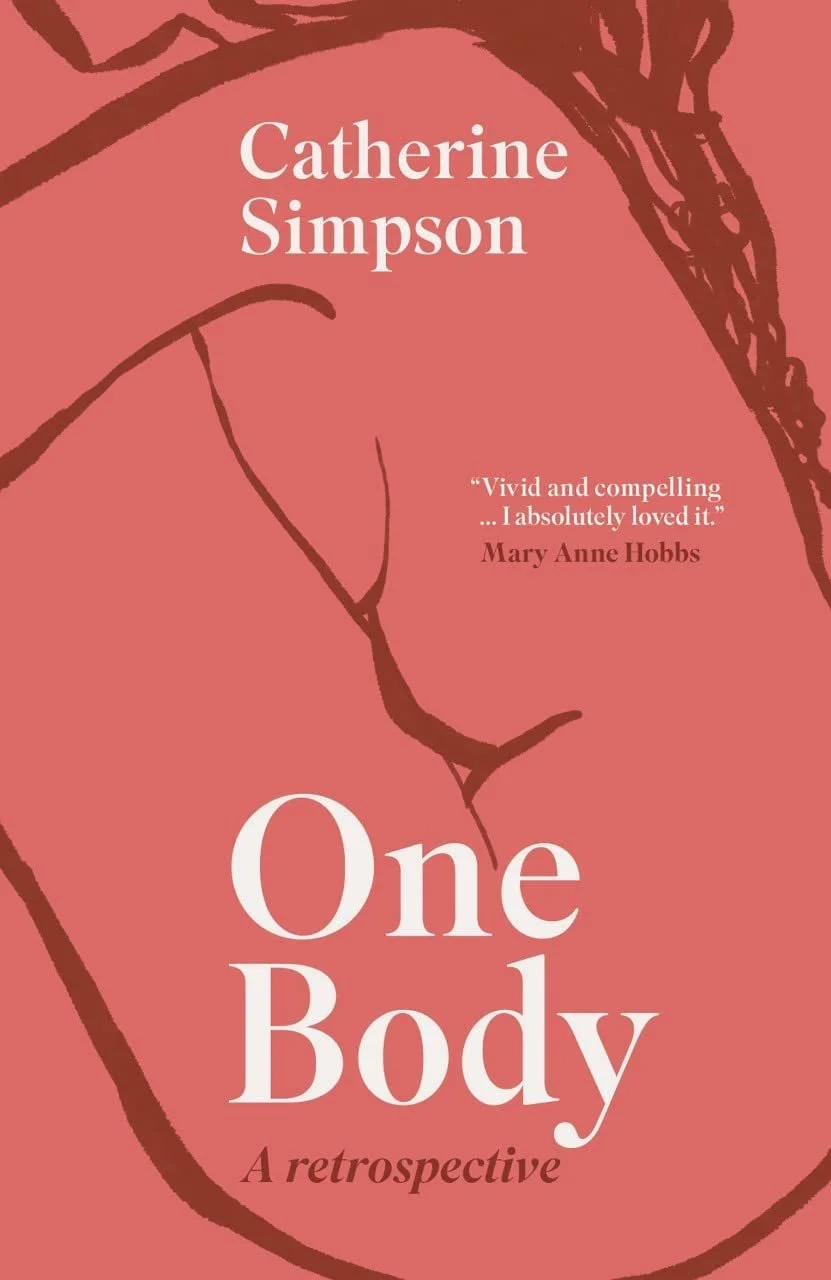

One Body, A Retrospective, Catherine Simpson.

A new diagnosis

In her book Catherine narrates her story of being diagnosed with breast cancer and her experience of surgery and treatment.

I’ve used this passage (p19-20) many times in teaching. I usually read it out loud while showing Matthew Krishanu’s picture that is reproduced below.

I had expected to see the hospital consultant, but it was a young woman with a blonde ponytail, who wore a badge saying houseman which I learned later was a junior doctor. As I entered the room she was poring over my notes. She talked as her eyes continued to scan. The page the results were back, and she read them out, but they were in a medical jargon I didn't understand.

The word cancer was not used but I gathered I needed an operation to remove what they had discovered. My mind snagged on this information.

So it was cancer

I had cancer

I was a woman with breast cancer

I remember nothing else of what she said and then she was gone. Fortunately nurse Lizzie was there again with the booklet, Understanding breast cancer in women.

She laid it on the desk, drawing asterisks besides invasive lobular breast cancer, then stage 1, then grade 2, then ER positive and PR positive

I was overwhelmed by both the blunt force of the cancer diagnosis and these incomprehensible details.

Lizzie explained a lumpectomy to cut away the tumour, an operation for which there was a six week wait.

She could see I was lost and trying to reassure me saying there were ladies we treat who are still walking around …..she waved the booklet for emphasis ……25 years after treatment.

I was 54 and not reassured; My mother died of cancer at 74 and it had felt too young then. Anyway, my father with 92 and living independently- having a long-lived parent makes anything less seemed like shortchange.

I asked about the lymph nodes- remembering the ultrasound technician’s concern about one of them. Lizzie explained we would not know whether the cancer had pass through the lymph nodes and possibly spread until after the lumpectomy, during which several lymph nodes would have been removed for analysis.

I was crushed that although I had a definite cancer diagnosis, the wait for clarity continued.

Much as Euro Disney had taught me to queue.

And being a civil servant had taught me to form-fill.

Cancer would teach me to wait.

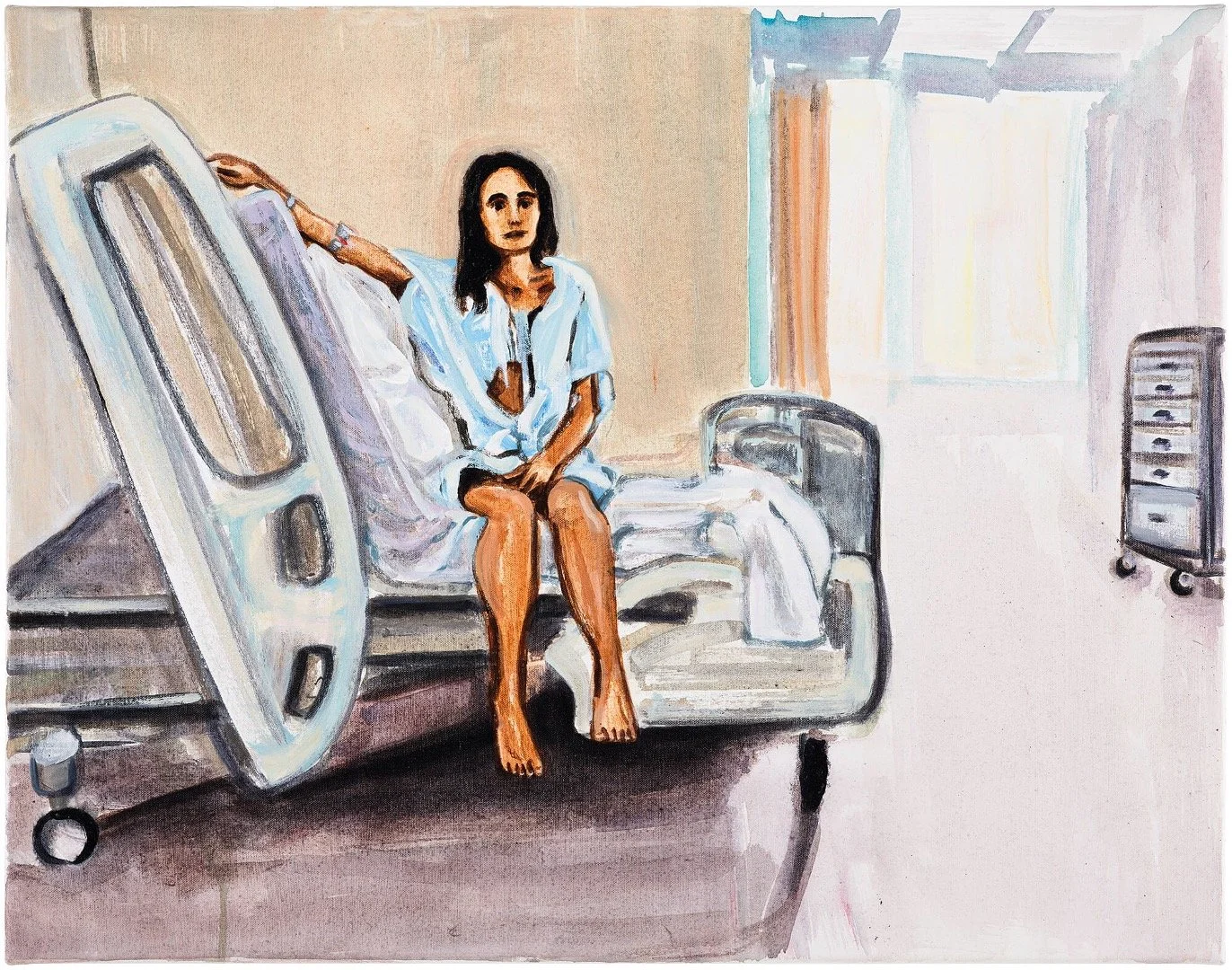

Girl on a Bed, Matthew Krishanu (2007)

Being a patient in hospital

What do you notice?

How do you think she feels?

What do you think she might be worried about?

What might be about to happen next?

What might you say to her if she was a patient you had been asked to see? (as a student or doctor)

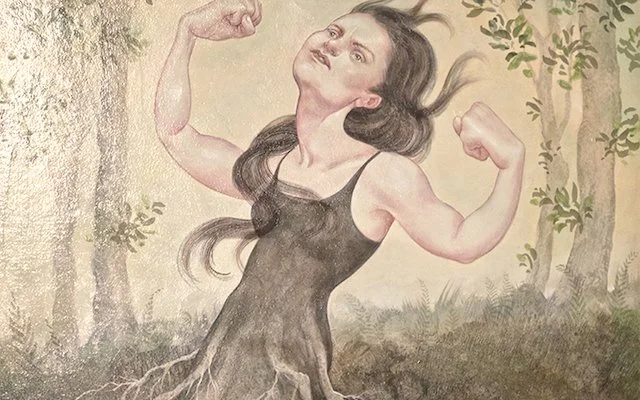

Strength, Anita Kunz

Living with a chronic illness

As part of The Framing OFF Through Art initiative, artist Anita Kunz created a piece of art for Jennifer Parkinson, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease at 32.

In what way do you think this painting conveys how Jennifer feels about her illness?

There are many other art resources across the pages of this website that communicate the suffering and experiences associated with chronic illness.

You have probably come across other resources online.

Take a moment to ‘Google’ Frida Kahlo’s painting, The Wounded Deer. I think this is an excellent visual metaphor for the suffering associated with illness and adverse life events. e

When Breath Becomes Air, Paul Kalanithi

Living with a terminal illness

When Breath becomes Air, is a non-fiction autobiography of neurosurgeon, Paul Kalinithi’s experience of living with and dying of lung cancer.

‘The tricky part of illness is that, as you go through it, your values are constantly changing. You try to figure out what matters to you, and then you keep figuring it out. It felt like someone had taken away my credit card and I was having to learn how to budget. You may decide you want to spend your time working as a neurosurgeon, but two months later, you may feel differently. Two months after that, you may want to learn to play the saxophone or devote yourself to the church. Death may be a one-time event, but living with a terminal illness is a process.’

There is another dimension to this book and that of the doctor as a patient.

Doctors don’t expect to become a patient and often find the experience unexpectedly challenging and distressing.

Unheard, Rageshri Dhairyawan

Doctors as patients

Rageshri’s book was written in response to her experiences as a patient. The key focus of her book brings us back to what I write at the beginning of this page- we can’t offer compassionate care to patients if we don’t first create an environment and culture in which their story can be heard and their suffering seen.

I heard Rageshri speak at a conference about her book which is due to be published in 2026- it’s on my ‘to buy and read list’.

Resource library - Books & Literature These books are all great resources to explore the patient perspective of illness.

-

Illness

by Harvi Carvel

-

Illness as Metaphor

by Susan Sontag

-

The Sleeping Beauties

by Suzanne O’Sullivan

-

The Sick Rose

by Wellcome CollectionYou can buy this at the Wellcome Collection or online. The bookshop at the Wellcome collection has a great selection of books about the art of medicine.

-

The Secret Scripture

Sebastian Barry

-

Between Two Kingdoms

by Suleika JaouadThis is Suleika’s story about living with leukaemia.

‘An inspirational memoir about what we can learn about life from a brush with death’.

-

The Island

by Victoria Hislop

-

An anthology of llness

by The Emma Press

A great collection of poems to use in teaching the patient perspective of illness.

prompt Now it’s your turn…

Think about the last patient you saw who was ill and try writing a short poem or piece of prose to reflect how you think they felt. This simple task builds empathy.

What is your own experience of illness?

Here is a short poem I wrote in response to experiencing ill health. You can see that Susan Sontags words resonated with me.

The line of illness

by Nicola Gill (me)

March 2017

The line is invisible

to doctors

who think

they understand

the pain

the fatigue

the loss of identity

that is illness

The line is a border.

Patients have no visa, no passport to cross back to the other side that is health.

Medical resourcesIn this section, I hope to capture articles and research that shows the value of using art resources in Medical Education to understand the patient perspective of illness.

page updated December 2025